The Arthurian Legend and Geoffrey Chaucer

Literature holds timeless universal human truths which can be read or listened without regard to historical context of its production and without regard to particular historical moment in which we read, listen and make meaning of it. It is the vehicle for the transmission of cultural knowledge and the primary means by which we gain access to others’ minds.

The usual forms of popular and traditional expression were oral literature, music, dance, mythology and festivals. Since ancient times, tribal chiefs, chamans, bards and story-tellers have been in charge of preserving and memorising the narratives of the past.

The earlier inhabitants of England, the Celts, passed on no written literacy to their conquerors, the Romans, since they had an oral literary tradition. Later on, the Romans brought to the island the art of writing through their historical literary accounts: Tacitus’s Germania (AD98) or St Jerome’s vulgate edition of the Bible (AD384). Later on, the Germanic tribes, the Angles, Saxons and Jutes invaded the island. They were illiterate people so their orally-composed verses were not written unless they formed part of runic inscriptions. When the Roman Empire faded, the Saxons did not have to change their Germanic tongue for Latin although Latin was the language of those who could read and write. The English learned to write only after they had been converted to Christendom by missionaries sent from Rome in AD 597.

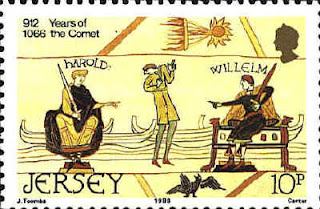

The Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest in 1066 was a turning point for England. It had several consequences on political, social, economic, cultural and literary ones. Literature in England was not only in English and Latin, but in French as well. It also developed in directions largely set in France. Epic and elegy gave way to Romance and lyric and English writing revived fully in English after 1360 and flowered in the reign of Richard II (1372-1399). It gained literary standards in London English after 1425 and developed modern forms of verse (in Chaucer in the fourteenth century), of prose (in Julian of Norwich and Malory in the fifteenth century) and of drama. The re-establishment of English meant that it was impinged with French language and culture.

Each century in the so-called Middle Ages has its own relevant contribution in this period. The 11th century is characterized by epic and elegy. The 12th century is characterized by romance and lyric, namely the Arthurian legend and courtly literature. The 13th century is mainly characterized by lyrics and prose and it is set up in context through medieval institutions and authorities in that period. The 14th century is mainly represented by the figure of Geoffrey Chaucer, besides its spiritual writing and secular prose.

The 11th century in literature

The linguistic situation during the 11th century and early 12th century is described as a period of bilingualism, ie the coexistence of two languages which were not wholly mixed up. The promotion of French was impinged by the close connection between Norman nobility in England and in Normandy, the expansion of the Duchy of Normandy under King Henry II rule, and the development of courtly literature by wish of Henry’s wife, Eleanor, among others.

The 12th century

When a new writing appeared in the 12th century, it was in an English which had become very different from that of the 11th century. The classical Old English verse died out and it revived in a different form, romance, and the prose developed in a lyric form. Romance is defined as a kind of medieval story originally from stories written in vernacular French. Actually, in c.1200 the Norman Layamon based his old English heroic poem Brut on the French Roman de Brut (1155) by Wace, a conon of Bayeux, who in turn based his work on Geoffrey of Manmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae.

Geoffrey of Manmouth wrote Historia Regum Britanniae in AD 1135. He unconsciously created the Arthurian legend by means of a historical romance. Arthurian literature belongs to the age of chivalry and the Crusades after 1100. However, it has been reported that Arthur existed in Britain when the Anglo Saxons arrived in 1497. according to the historian Gildas there was a Romanized Celtic chiefland called Ambosious Aureliano, who became a Celtic hero against the Saxon invasion in west of Britain. Another British author reported that this chiefland defeated the Saxons and led his warriors to victory in twelve successful battles against the Saxons, the later taking place at Mons Badonicus in today’s Wales. Later oral legends created King Arthur, his knight of the Round Table, Camelot and the Quest for the Grail. Geoffrey’s work was put into English by Layamon as a legendary story of the island of Britain. It was written in 14000 lines and makes no distinction between the British and the English.

The 13th century

Shortly after 1200, England lost an important part of her possessions abroad. It lost Normandy. This brought about important consequences such as the loss of prestige of Norman- French and Anglo- Norman. The properties of barons living in England in French soil were confiscated by the king Phillip II of France. This implied that the nobility gradually relinquished their continental states and a feeling of rivalry developed between the two countries accompanied by an anti-foreign movement in England and culminating in the Hundred Year’s war. Now French was no longer necessary to the upper class. The English nobility grew a new collective feeling of their insular identity and soon considered themselves as English. This nationalistic feeling did not extend to the courtly nobility. Henry III 1207-1272) married Eleanor of Provence who brought with her to England a hot of French relatives so as to be surrounded by French nobles and prelates. Therefore, French knight in charge of castles oppressed the barons of Norman- English origin. The gap between the aristocracy (nobility at court) and the barons (rural nobility) was the reason for the Baron’s War (125- 12 65) in which the barons rebelled so as to claim a grater participation in and supervision of royal government. This claim was kept in the Provision of Oxford (1259). The loss of prestige of Norman French reinforced the functional use of English even in the upper classes.

In the Middle Ages, like in other periods in history, culture and art in Europe were promoted by the Church. The clergy were the source of education at that time as well as of arts and literature. Institutions and mental habits shaped this new English literature. Bishops and priests who lived in the secular world brought the Word and the sacraments to the people, and higher education was namely provided by religious monks, nuns and later, friars. This education was given at schools which were set up in monastic cathedrals in cities such as Winchester, Canterbury or Westminster. From the 12th century intellectual initiative began to pass from schools to universities and therefore, the teachings of the Church were to be modified by new learning. Intellectual activity in the new universities was led by friars who were members of the new orders founded by St Dominic and St Francis. So literacy came through the Church. In a Christian world all type of writing gained a Christian function and soon, much of the best English writing was wholly religious, such as that of the mystic Julian of Norwich or William Langland’s Piers Plowman. Medieval drama and much medieval lyric were created to spread the gospel to the laity.

Academic learning inspired clerical literature such as the Owl and the Nightingale (early 13th century) which became the bird of love in Provençal lyrics. Hundreds of medieval lyrics remain in manuscripts which can be roughly dated, but composition and authors are usually unknown.

Middle English prose of the 13th century continued in the tradition of Anglo-Saxon prose—homiletic, didactic, and directed toward ordinary people rather than polite society. The Ancren Riwle (c.1200) is a manual for prospective anchoresses; it was very popular, and it greatly influenced the prose of the 13th and 14th cent. The fact that there was no French prose tradition was very important to the preservation of the English prose tradition.

In the 13th century, the romance, an important continental narrative verse form, became popular in England. It drew from three rich sources of character and adventure: the legends of Charlemagne, the legends of ancient Greece and Rome, and the British legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Romances were tales of adventurous and honourable deeds. At first they were deeds of war and later on, deeds to defend ladies or to fight for them. Soon they developed into courtly literature. The warrior gave way to the knight, and when the knight got off his horse he wooed the lady. The pursuit of love grew ever more refined in courtly literature. Ideals of courtly love, together with its elaborate manners and rituals, replaced those of the heroic code; adventure and feats of courage were pursued for the sake of the knight’s lady rather than for the sake of the hero’s honor or the glory of his tribal king. Popular stories made reference to classical themes full of marvels. Romance is a lasting legacy of the Middle Ages, not only to works of fantasy in later centuries (Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene, the Gothic novel, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Samuel Richardson’s Pamela) Original English romances based upon indigenous material include King Horn and Havelok the Dane, both 13th-century works that retain elements of the Anglo-Saxon heroic tradition. French romances, notably the Arthurian romances of Chrétien de Troyes, were far more influential than their English counterparts. In England French romances popularized ideas of adventure and heroism quite contrary to those of Anglo-Saxon heroic literature and were representative of wholly different values and tastes.

Continental verse forms based on metrics and rhyme replaced the Anglo-Saxon alliterative line in Middle English poetry (with the important exception of the 14th-century alliterative revival). Many French literary forms also became popular, among them the fabliau; the exemplum, or moral tale; the animal fable; and the dream vision. The continental allegorical tradition, which derived from classical literature, is exemplified by the Roman de la Rose, which had a strong impact on English literature.

The 14th century

During the 14th and 15th centuries, new historical events, such as the Hundred Years’ War, the Black Death and the Peasants’ revolt reinforced the national feeling which has ensued the loss of Normandy and led inhabitants of the island to a general adoption of English. The Hundred Years’ War (13337- 1453) came up due to the question of succession to the French crown (claimed by Edward III OF England against the house of Valois, Philip VI who was appointed King of France). This war made English people realize that French was the language of the enemy court. That was one of the causes contributing to the disuse of French. The outcomes of the war were the development of national consciousness among the English and a general feeling of hatred against France, French customs and the French language.

The bubonic and pneumonic plague which ravaged Europe in the 14th century reached England in 1348. As a result, about one third of Europe’s population and almost half of the population of Britain died. The effects of the Black Death were felt at all levels particularly the social and economic ones since the drastic reduction of the amount of land under cultivation became the ruin of many landowners. The shortage of labour implied a general rise in wages for peasants and consequently, provided new fluidity to the stratification of society and afforded a new status to the middle and lower social classes, whose native language was English. These classes (middle and lower) rebelled against the imposition of a poll tax and particularly against the Statute of labourers, which tried to fix maximum wages during the labour shortage following the plague. The peasants’ revolt, as this rebellion is known, also contributed to increase the social relevance of the labouring classes and indirectly conferred importance on their native tongue.

The consequences of these events were to be felt in a general adoption of English in the late 14th century. It became recognized in official, legal, governmental and administrative affairs. The historical events led to a gradual use of English in these high domains. Non religious prose had been used for practical matters in the 12th century. But in Richard II’s reign English came into general use. His reign saw the flowering of a mature English poetry in Middle English. Arthurian verse romances were spirited in the revival of alliterative verse. The poetry of the alliterative revival, the unexplained re-emergence of the Anglo-Saxon verse form in the 14th century, includes some of the best poetry in Middle English. It produced at least two crucial poems, the moral allegory Piers Plowman (1377) by William Langland and ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’ which was found with three other poems, Patience, Cleanness and Pearl, in the Gawain manuscript (c1390) The Christian allegory The Pearl is a poem of great intricacy and sensibility that is meaningful on several symbolic levels. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, by the same anonymous author, is also of high literary sophistication, and its intelligence, vividness, and symbolic interest render it possibly the finest Arthurian poem in English. Other important alliterative poem is the alliterative Morte Arthur, which, like nearly all English poetry until the mid-14th century, was anonymous.

The most important contributions to the literature development of this century were Chaucer and Gower. John Gower (1330- 1408) contributed with the appearance of an assured syllabic verse in his long poems. He wrote in three languages, English, French and Latin. Geoffrey Chaucer contributed with the establishment in English of the decasyllabic verse of France and Italy. He wrote only in English, what gave a deeper social reach that French or Latin at that age.

Chaucer was probably born in 1343 in London. His father was a wine merchant. He had only one sister, who was a nun. In 1357 he became a king’s man (1374- 1391), that is, a professional royal servant in the household of Prince Lionel, later duke of Clarence. During these years, Chaucer was frequently employed on diplomatic missions to the continent, visiting France, Spain and Italy in 1372-3 and 1378. He was also a diplomat and travelled on the king’s business. He lived in London and Kent, surviving the Black Death, the French Wars and the Peasants’ Revolt, the Lords Appellants’ challenge to Richard II, and Richard’s deposition by Henry IV. In 1359-60, he was with the army of Edward III in France where he was captured by the French but ransomed later. He married Philippa Roet, daughter of a Flemish knight, who was a lady in waiting to Edward III’s queen. She was probably the sister of John Gaunt’s third wife. The official date of Chaucer’s death is October 1400. he was buried in Westminster Abbey.

His literary activity is often divided into three periods: his early works, the Italian period and his mature works. The first period includes his early works to 1370 which are based largely on French models ofdream visions. The Book of the Duchess (1368-72), an allegorical lament written on the death of Blanche, wife of John of Gaunt, and The Romaunt of the Rose before 1372, a partial translation of the Roman de la Rose, are based on Guillaume de Machaut.

The second period up to 1387 is called his Italian period because during this time his works were modelled primarily on Dante and Boccaccio. Major works of this period include The House of Fame (1378-83), recounting the adventures of Aeneas after the fall of Troy, The Parliament of Fowls (1380-82), which tells of the mating of fowls on St Valentine’s Day and is thought to celebrate the betrothal of Richard II to Anne of Bohemia, and a prose translation of Boethius’ De Consolatione Philosophiae. Also among the works of this period is Troilus and Criseyde (1382-86) based on Boccaccio’s Filostrato, one of the great love poems in the English language in which he perfected the seven-line stanza later called rhyme royal.

Chaucer’s mature and last work, The Canterbury Tales, is today his most popular work. The idea of a frame story, that is, a story within a story, comes from a long tradition: The Arabian Nights and The Decameron. Originally he proposed 124 stories but he wrote 24. it introduces a group of pilgrims travelling from London to the shrine of St Thomas Becket at Canterbury, who was killed by agents of Henry II in 1170 at the altar of his cathedral. To help pass on time on the two- day ride to the shrine, the thirty pilgrims decide to tell two tales each on the way and two on the way back. Together, the pilgrims represent a wide cross section of 14th century English life.

It is set in 14th century London which is considered to be one of the medieval period’s great centres of commerce and culture. Society was still very strictly ordered, with the Knight and noles having all power in political affairs and the Catholic Church having all authority in spiritual matters. However, trade and commerce with other nations had expanded and consequently gave rise to a new and highly vocal middle class comprised of merchants, traders, shopkeepers, and skilled craftsmen. Their newly acquired wealth, their concentration in centres of commerce and their organization into guilds gave this newly emerging class increasing power and influence. Chaucer showed interest in middle class characters such as a cook, a carpenter, miller, priest, prioress, pardoner, lawyer, merchant, clerk, physician, who reflect the rise of the middle class in the 14th century. Literature hen moved from the questions of romance to a more domestic vision. Chaucer is interested in individuals, in their foibles, in middle class people. The subject matter in the tales is sex, lust, greed, jealousy, native cunning, the credulousness of the stupid, marital problems, infidelity, and corruption of the church among others.

By the 15th century, during Henry V’s reign (1413-1422), the English language was officially used at both the oral and written levels in most fields, except legal records which were still written in Latin, the Statutes of Parliament (in French until 1489) and in ceremonial formulae (still in French). Yet, many literary productions reinforced the national feeling and led to a general adoption of English.

The 15th century

The 15th century is not distinguished in English letters, due in part to the social dislocation caused by the prolonged Wars of the Roses. There was good English writing particularly lyric and drama and prose, but no major poet. Some authors worth mentioning are John Lydgate (1370- 1449) with his work

Troy Book, written for Henry V, and Thomas Hoccleve (1369-1426). Other poets of the time include Stephen Hawes and Alexander Barclay and the Scots poets William Dunbar, Robert Henryson, and Gawin Douglas. The poetry of John Skelton, which is mostly satiric, combines medieval and Renaissance elements. The decasyllable lost its music as words altered in accent and inflection. English borrowed prestige words from Latin and French and doubled its resources and its eloquence. It paired English and Romance synonyms. Besides, new literary streams and events were entering this century.

In drama,

mystery and morality plays became commonplace. The miracle play was a long cycle of short plays based upon biblical episodes. The morality play originated as an allegorical drama centering on the struggle for man’s soul. Religious lyrics and Scottish poetry became important as well. The most important event that caused a magnificent turning-point in literature was the printing press with which quality marketing began. William Caxton introduced printing to England in 1475 and in 1485 printed Sir Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. This prose work, written in the twilight of chivalry, casts the Arthurian tales into coherent form and views them with an awareness that they represent a vanishing way of life. The finest of the genre is

Everyman.